A Short Biography of Catalina de Erauso: Nun, Soldier, Transvestite

[Delivered Orally, Presentation Format]

Imagine you’re fifteen years old; you’re cooped up in a Spanish convent, reeling after a beating from an older nun. Your father and brothers left you here at the age of four to pray the rosary while they’re all off fighting for the Spanish Military in the New World. With dread you count the days left ‘till you take your vows, and each night look up at the stars, dreaming, praying: “Dear God … I wish I could kill people... and swordfight... and hit on other women.”

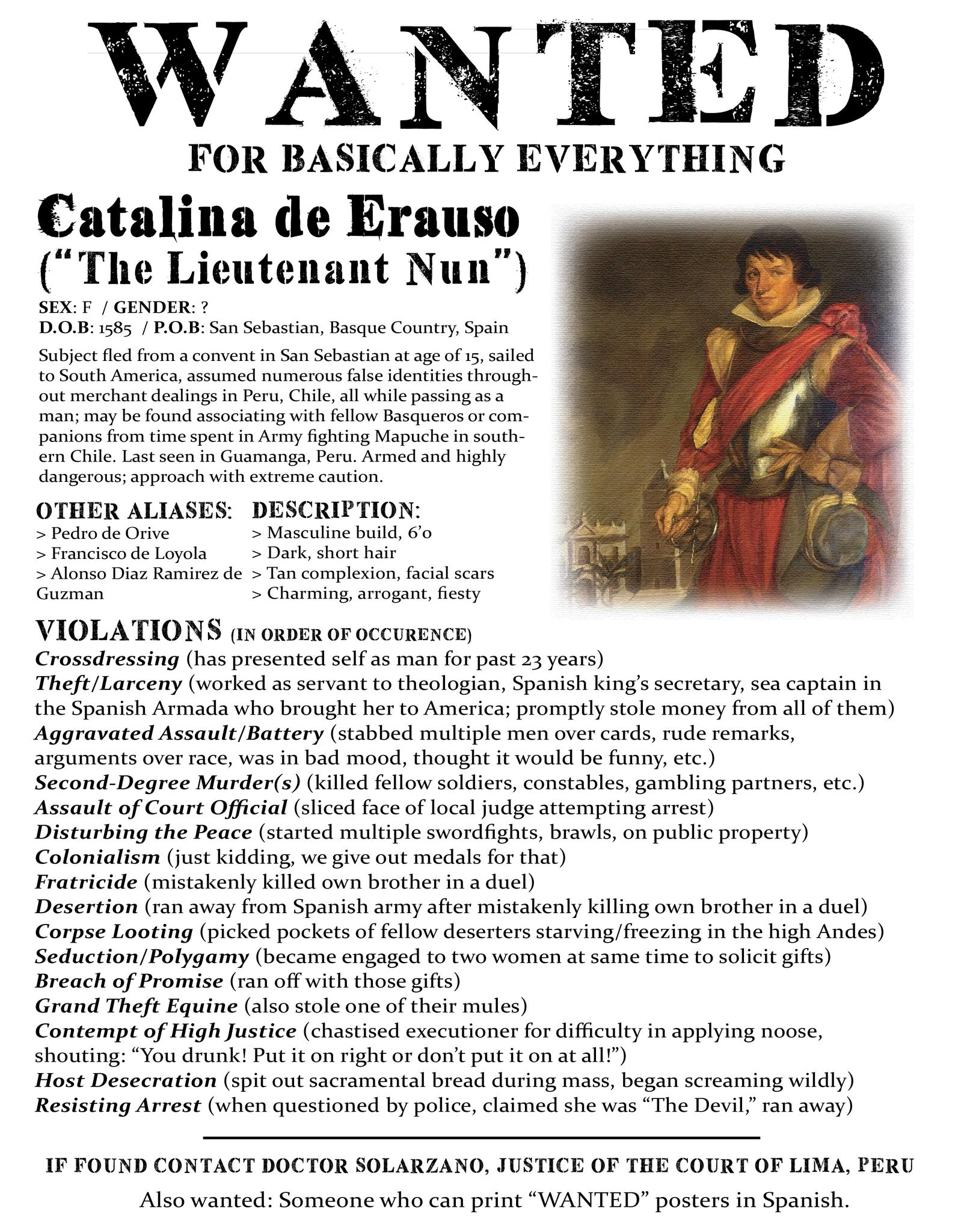

Catalina de Erauso was a Spanish folk hero, and one of the first women to write her own autobiography, our main source for her life, so I’ll be discussing her through that lens: “The Lieutenant Nun: Memoirs of a Basque Transvestite in the New World.”

As the title might imply, she writes that in 1600 she stole the keys to her Convent and pulled an Arya Stark, cutting her hair short and sewing together breeches from her old petticoat to pass as a man. In class we’ve discussed how clothing in the Early Modern period was an extension of one’s wealth and identity; by fashioning a new outfit, Catalina steps into new role entirely, one that allowed her incredible privilege; the clothes quite literally made the man.

After sailing to Panama in 1603, she finds a job managing a store for a merchant in Peru after the two of them survive a shipwreck together and then quickly loses that job when someone sits too close to her at the theatre and she responds by stabbing them. Relatable! This would become a trend for her. She’d travel to a new town, wind up in a swordfight, a local official would try to arrest her, she’d stab them too, and then she’d run behind the nearest Bishop asking for asylum. Unlike England, the Spanish in America largely stuck with Catholicism, with the Counter-Reformation really taking hold there at the time.

Anyways, her next merchant job in Lima, Peru goes no better, as Catalina is fired after her boss walks in to find her head nestled in his sister-in-law’s skirt. If born today, Catalina would probably identify as a transgender man. She fully embodies ‘masculinity’ for most of her life, even revelling in it. However, that label didn’t exist in the Early Modern Period. I’m using female pronouns simply because even feminist scholars go back and forth on this. To call Catalina a ‘man trapped in a woman’s body’ is to reach across centuries of culture, gender, and gaps in knowledge, to place her into a modern identity of which she’d have no knowledge.

Anyways, after that, she tries her luck at the family business by joining a company of soldiers in Lima, Peru. The Spaniards were still very much carrying the fire of the Conquistadors, and Catalina helped wage war against the native (MAH Poo Chay) Mapuche over the colonization of southern Chile. After a quick promotion to Lieutenant, she spends six months “slashing and burning Indian croplands” in Puren, later assaulting a Mapuche village to steal their gold, quote, “slaughtering all the way … butchering so many of them that the blood ran like a river.” While it is tempting to romanticise Catalina as a subversive outsider or feminist hero, she was painfully complicit in the colonial project.

She eventually deserts the army after accidently killing her brother in a duel on a moonless night, whoops, becomes a serial gambler, and then in 1623 finally ends up in an escalating chain of cop-killing through Peru; wanted posters go up and she’s forced to play the only card she has left. To the delight of the bishop protecting her, the nuns confirm that not only is she a woman, she’s an “intact virgin,” which of course means that she’s right with the Lord and all is forgiven. I’m not kidding, that’s what happens.

Her story rapidly spreads across the Spanish world, she becomes a folk hero, in August 1625 she’s granted a yearly pension by King of Spain and then meets Pope Urban the Eight who gives her permission to wear men’s clothing, after which she writes her memoir and becomes a mule-driver back in America.

In short, a lot of this sounds made up! While baptism certificates and army papers do attest to the broad strokes of her life, it’s scholarly consensus that, in writing her memoirs, she foregoes “fact” to play into the Spanish Picturesque genre and Baroque style popular at the time – most notably in Don Quixote, written a few years before. She abandons chivalric moralizing in favour of realistic detail and exaggerated motion, placing herself at the centre of a drama of discovery: a common, roguish hero living by her wits in a vast New World.

Regardless of her moral faults, this is actually kind of incredible; Catalina takes ownership over her own story and how it’s told in an era when most women didn’t even have a voice; she writes herself. She was unabashedly herself. And you kinda have to respect that.

Post a comment