A Special Presentation of the Ancient Earth Historical Society

INTRODUCTION:

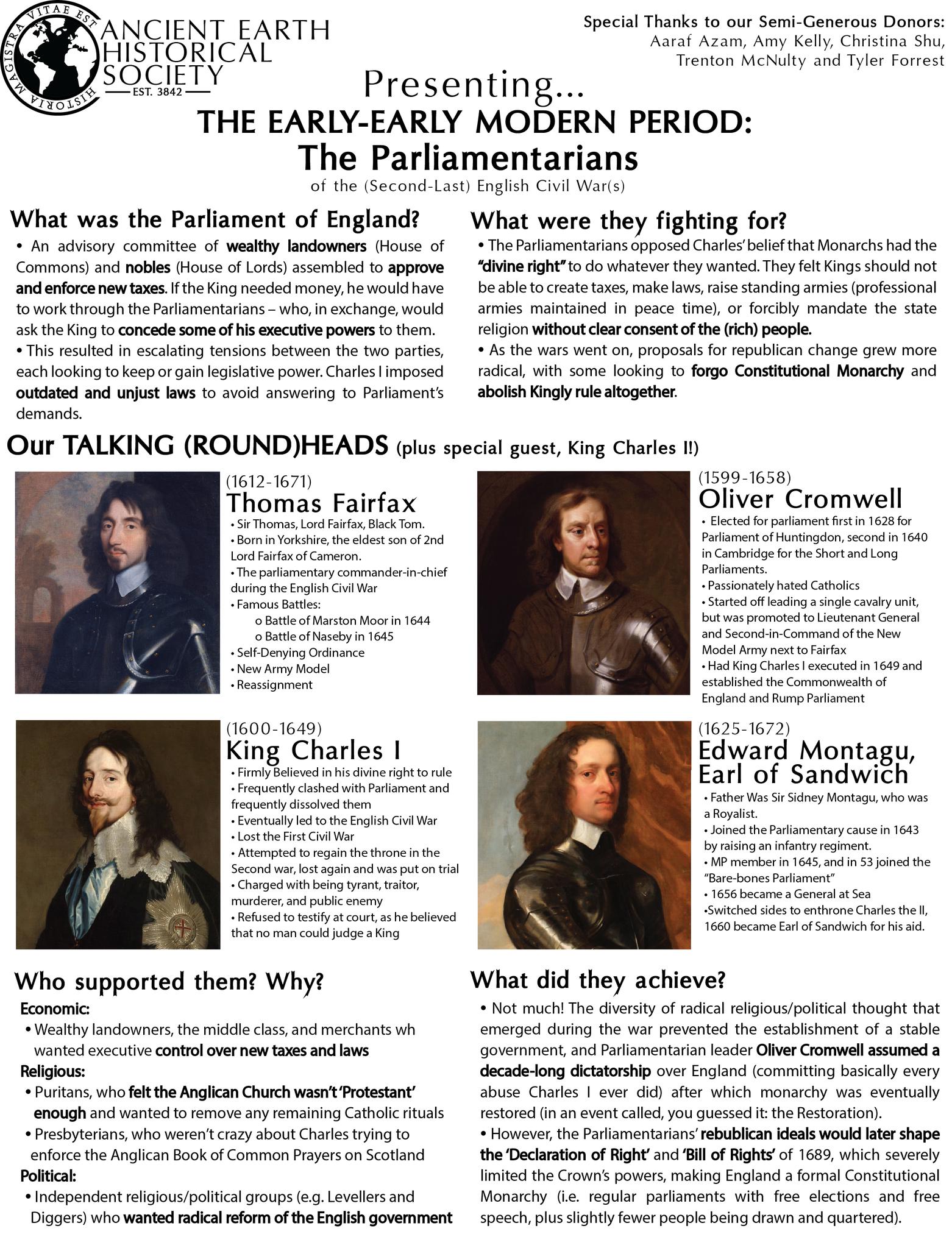

I’d like to welcome and thank you all for attending this special presentation of the Ancient Earth Historical Society. As I’m sure you’re all aware, the Society prides itself on providing accurate, personal and decidedly in-dispassionate human and post-human historical perspectives; which is why our historical technicians have gone back in time to – at moment of death – scan the brains of Thomas Fairfax, Oliver Cromwell, Edward Montagu, and Charles I, in order to give you their perspective on the English Civil Wars.

Due to unfortunate budget cuts to the Interstellar Endowment for Arts and Humanities, we have been unable to manufacture body sleeves in the historical likenesses of our guests and have instead been forced to put each man’s consciousness in one of several – as you can clearly see – defective android units from storage; we apologize in advance for any perceived technical glitches or lapses in coherent thought.

Our topic today, as mentioned, is the English Civil War – specifically from the side of the winners, if you could call them that: the Parliamentarians or Roundheads (so named for the incredible style of their Puritan soldiers who cut their hair short in a statement against the stuffy long-haired nobles).

Anyways, to introduce this group, it’s important to establish what the Parliament of England actually was.

Originally, it was simply an advisory committee of nobles and feudal landowners, temporarily summoned at the King’s leisure and dissolved whenever he saw fit.

However, these landowners had leverage over the King in that, as landowners, the Crown relied on them to collect taxes from those living on their land; Monarchs simply didn’t have the resources to march around the entire English countryside asking for money. Thus, they allowed these landed gentlemen (or “gentry”) to elect representatives to the House of Commons; they, along with the House of Lords – high-ranking nobles and bishops – made up the Parliament of England.

By the 17th Century, tensions between the King and his parliaments became increasingly strained. If he wanted money – say, if he was bored and felt like going to war – he would have to work through the Parliamentarians – who, in exchange, would occasionally ask the King to concede some of his executive powers to them.

As Charles I will tell you, he thought this deal was kind of a bummer, and imposed outdated and unjust laws to avoid answering to the gentry’s demands – which just made the House of Commons and House of Lords band together (which was kind of a big deal, considering how stuffy nobles can be) to restrict his power even more.

Eventually, Parliamentarians like Fairfax, Cromwell, and Montagu had enough. “You know, Charles, I don’t think you should have the “divine right” to do anything without the express consent of all the other rich people!”

When war broke out, they galvanized all the different groups with grievances towards the state and how it was run. On the economic side, you had the gentry, middle class, and merchants who wanted control over the creation of new taxes and laws; you had religious groups like the Puritans, who thought the Church of England just wasn’t Protestant enough and needed to be purified of its ‘Catholic’ rituals, and also Charles married a Catholic which was very scary; the Presbyterians, who wanted religious freedom in that they were also not cool with the Church of England and rebelled at Charles’ attempts to impose it on Scotland; and finally, independent groups with radical political ideas – like the Levellers, who thought, “Hey guys, how about democratic representation for all households?” Or the Diggers, who thought way too big, suggesting agrarian proto-anarchism / socialism / equal rights (no one liked the Diggers). Or the apocalyptic Fifth Monarchists, who thought the new government would usher in the rule of Christ and His saints.

In summary, the Parliamentarians and their supporters wanted a lot of different things, with the common sentiment being that they didn’t like absolute rule or Charles the first.

Which brings us to our first speaker, who will provide an initial outsider’s perspective on the problems the Parliamentarians seemed to have had with his administration...

[Group members assume the roles of different historical figures and recite facts about their lives; I lean awkwardly against a blackboard for 10 minutes until it's my turn to speak again.]

CONCLUSION:

Well – that concludes our presentation. I’d like to thank each of our guests for taking the time to speak to us to today out of the kindness of their own synthetic hearts and also under threat of deletion.

But the question remains: What did the Parliamentarians achieve? What was the War for?

As it turns out, not a whole lot. The diversity of radical religious and political thought that emerged during the war prevented the establishment of a stable government, and, as Oliver discussed, brought things right back to the way they were before.

But while the war in itself may not have been immediately useful, the ideas behind it – theidea that the Crown should only rule through the consent of the governed, that power should rest in legislature and not personal whim – would eventually go on to shape the ‘Declaration of Rights’ and ‘Bill of Rights’ at the end of the century, which severely limited the Crown’s powers, making England a formal Constitutional Monarchy: one with regular parliaments and free elections, paving the way for the parliamentary democracy Britain would eventually become.

Which is neat!

Post a comment